Women and drugs: health and social responses

Introduction

This miniguide is one of a larger set, which together comprise Health and social responses to drug problems: a European guide. It provides an overview of the most important aspects to consider when planning or delivering health and social responses for women who use drugs, and reviews the availability and effectiveness of the responses. It also considers implications for policy and practice.

Last update: 8 March 2023.

Contents:

Overview

Key issues

Women make up approximately a quarter of all people with serious drug problems and around one-fifth of all entrants to drug treatment programmes in Europe. They are particularly likely to:

- experience stigma and economic disadvantage, and have less social support;

- come from families with substance use problems and have a substance-using partner;

- have children and be responsible for their care, which may play a central role in their drug use and recovery; and

- have experienced adverse childhood experiences, in particular sexual and physical assault and abuse, and have co-occurring mental disorders.

There are a range of sub-groups of women with drug problems that have specific needs. These sub-groups, which often overlap, include pregnant and parenting women; women involved in the sex trade; LGBTQIA+ women, women from migrant or ethnic minority backgrounds; and women in prison.

Responses

- Specific services for women offered in female-only or mixed-gender programmes, delivered in welcoming, non-judgmental, supportive and physically and emotionally safe environments, while promoting healthy connections to children, family members and significant others and integrating childcare services.

- Collaboration between drug treatment and mental health services to address co-occurring substance use issues and mental health needs.

- Services for pregnant and parenting women, dealing with drug use, obstetric and gynaecological care, infectious diseases, mental health and personal welfare, as well as providing childcare and family support.

- Measures to overcome the barriers to care for women involved in the sex trade, such as providing evening opening hours, mobile outreach services and open-access support.

- Sensitivity towards ethnic and cultural aspects and the possibility of interpreter services when needed.

European picture

- The complex, overlapping issues faced by many women who use drugs require coordinated and integrated services. Across Europe, drug use, mental health networks and social services are often separated. Collaboration relies on the goodwill of stakeholders and cooperation at the individual level.

- While no systematic data have been collected on the availability of gender-mainstreaming responses to drug-related problems in Europe, a number of interventions have been developed that address the specific needs of women who use drugs.

Key issues related to women and drug use

In the Europe Union, it is estimated that a little over 30 million women and 50 million men aged between 15 and 64 have tried an illicit drug at some point in their life. Generally, the gender difference in overall drug use is smaller among young people, and this gap appears to be decreasing among younger age groups in many European countries. However, for more intensive and problematic forms of drug use, the difference between women and men is larger. Little information is available on other gender identities, such as transgender and non-binary people who use drugs but there are some data to suggest that they may face significant barriers to accessing health care.

Women make up approximately a quarter of all people with serious illicit drug problems and around 20 % of all entrants to specialist drug treatment in Europe. In some studies women have been found to be more likely to access treatment because of needs arising from pregnancy or parenting, or because of women’s greater willingness to seek care. However, other studies have found that women are less likely to seek specialised services than men because of the double stigma attached to both drug use in general and being a woman with a substance use problem in particular. The extent and nature of the treatment gap within different regions and sub-groups in Europe requires further study.

In many respects, women and men with drug problems differ in their social characteristics, living conditions and drug use patterns, in the consequences of their substance use and in the progression to dependence. Women present unique concerns that are sex- and gender-related, although many drug services remain male-oriented.

Specific problems include:

- Stigma: Women are stigmatised more than men for using drugs because they are perceived as contravening their gender roles, as the expected current or future social roles as mothers and caregivers. The internalisation of stigma can exacerbate guilt and shame, while discriminatory and gender-blind services may deter help-seeking.

- Socioeconomic burdens: These can be heavier for women who use illicit drugs because they tend to have lower employment and income levels. The cost of drug treatment may be a barrier if services are not provided by the state and there is no insurance coverage. Transport costs may also impede access to treatment.

- Social support: Women who use drugs may have access to less social support than men who use drugs because they are more likely to come from families with substance use problems or have a drug-using partner.

- Children: Among treatment entrants, women are more likely than men to live with their children. The absence of childcare options can therefore represent an important barrier to service access. Maintaining or improving relationships with children is very important and may play a central role in women’s drug use and recovery.

- Drug-using partners: Having a partner who uses drugs can play a significant role in women’s drug use initiation, continuation and relapse. It may also affect women’s risk of exposure to blood-borne viral infections and violence. Substance-using men may sometimes be unsupportive of their partners seeking treatment, and women may fear the loss of the relationship if they engage with such services.

In addition, compared with their male counterparts, women who use drugs have been found to be more likely to report experience of adverse childhood experiences (e.g. sexual and physical assault and abuse) or gender-based violence as adults, such as intimate partner violence.

Among people who use drugs, post-traumatic stress disorders and other mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression, are more common among women. Compared with men, women with psychiatric comorbidity are also more frequently reported as having a primary mental health issue followed by a drug-use problem. As a consequence, the exclusion of persons with a dual diagnosis from certain services may impact more on women than men.

Women who inject drugs have specific vulnerabilities to blood-borne viral infections. They are often found to have a higher HIV prevalence than men because they are more likely to share injecting equipment, especially with their intimate partners. They are also more likely to report trading sex for drugs or money and may have difficulties negotiating condom use with sexual partners.

A number of sub-groups of women have particular needs and may require specific responses.

Women involved in the sex trade: Participation in the sex trade is often intertwined with drug use; for example, in some countries it is estimated that between 20 % and 50 % of women who inject drugs are involved in the sex trade. Many women who trade sex for drugs have limited power to practise safe sex or follow safe injecting practices and are at risk of experiencing violence and imprisonment. These women also face a greater degree of stigma, both through their drug use and involvement in the sex trade.

Women victims of gender-based violence: Experiencing gender-based violence is a risk factor for the development of drug-related problems. However, systematic data on gender-based violence are lacking at the European level. Women with drug problems are commonly found to have been victims of gender-based violence, including experiencing sexual abuse as children. In such cases, drug use may have started as a way to alleviate the trauma of sexual violence. Moreover, women with drug problems may experience gender-based violence in the context of drug use, through engaging in the sex trade or in their intimate relations. Women’s risk of exposure to intimate partner violence is thought to be higher when they, their partners, or both are involved in substance use. Women may also be victims of drug-facilitated sexual assaults, where violence is perpetrated on a woman who is under the effects of drugs, whether these substances were consumed voluntarily or without the subject’s knowledge or consent.

Women in prison: Many women in prison have a history of drug use disorders, with higher rates of drug use prevalence commonly reported compared to men for most substances. There are often no or limited services available in prisons for women seeking help for substance use disorders, and as such their psychological, social and health care needs often go unmet. Prisons are also high-risk environments for the transmission of blood-borne infections, but access to clean syringes is rare (see Prison and drugs: health and social responses). This may have a greater impact on women than men because, in Europe, female prisoners are more likely to report injecting drugs. Assessing the needs of women in detention, increasing the availability of appropriate responses and ensuring continuity of care on release are priority areas for the development of responses in this setting.

Pregnant and parenting women: Pregnancy and motherhood can be both a strong motivator for and a barrier to recovery. Many forms of drug use in pregnancy may adversely affect the unborn and new-born child. Guidelines now exist for the clinical management and use of opioid agonist medications during pregnancy and the perinatal period for women who use opioids. In addition to stigma, shame and guilt, drug-using women may fear having their children taken away. Women often have a pivotal role in facilitating health or social care for family members but may be afraid to contact services themselves. They may also be unable to access the support they need because of family responsibilities and a lack of appropriate childcare options.

LGBTQIA+ women: Women who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, pansexual, allies or other gender or sexuality (LGBTQIA+) may face discrimination, social stigma and a greater risk of being subjected to violence and aggression. They are also more likely to suffer anxiety, loneliness and comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders. They may fear displays of homophobic behaviours from health services staff and other patients and thus be hesitant in seeking care. These women in particular are likely to require inclusive interventions that address their specific needs and provide them with a safe environment.

Women from migrant or minority ethnic backgrounds: These women may encounter additional difficulties in accessing treatment services, such as language barriers or treatment approaches that may conflict with their religious beliefs. Some migrant women may have been trafficked and experienced trauma from war and violence in their homelands or en route. Migrants’ immigration status may also affect their eligibility to access services, and they may experience racism and discrimination. Careful consideration must be given to ethnic, cultural and religious diversity when responding to the needs of women from migrant or minority ethnic backgrounds.

There are still large knowledge gaps about women’s drug use. Research studies do not always include women and may not disaggregate data by gender or address gender issues. Most research on drug use among women of child-bearing age only deals with those using opioids, and more research is needed on other patterns of drug use among women (such as the consumption of cannabis, non-medical use of medicines and polydrug use); substance use among other specific groups of women (as most research focuses on mothers and caregivers); and the intersection between drug use and other problems often experienced by women who use drugs.

Responses to drug-related problems among women

The complex, overlapping issues faced by many women who use drugs require coordinated and integrated services. A gender-responsive approach is important to meet the needs of women who use drugs. Consideration of women’s needs should be incorporated into all aspects of service design and delivery: structure and organisation, location, staffing (including access to female practitioners in all services), development, approach and content.

These programmes may be female-only or mixed-gender programmes that include specific services for women. Staff competency could be fostered through education, training, skills development and adequate supervision. Community agencies (e.g. the child welfare system and health care providers) may also receive training to enhance awareness, identify women who use drugs and provide interventions or referrals, as necessary.

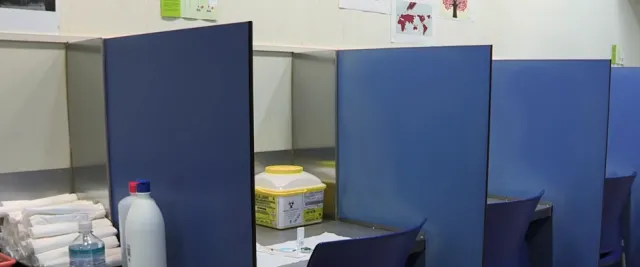

Because of the high levels of stigma and trauma experienced by women who use drugs, it is important that services are welcoming, non-judgmental and supportive, as well as taking a trauma-informed approach in order to provide women with a physically and emotionally safe environment. Services that aim to be holistic and comprehensive are likely to be better equipped to address the multiple issues that women face.

Specialised women-only services are provided by women for women and are tailored to their specific immediate and long-term needs. They have an important role in the care of women, particularly those who have experienced intimate partner violence, substance use problems or homelessness. These services often take a trauma-informed treatment approach that has several aims: to recognise the signs and symptoms of trauma in patients (and staff) and the role this can play in women’s lives; to avoid the repetition of trauma; and to restore feelings of safety and self-worth. For women at continuing risk of violence, a multi-agency, multi-sector approach is essential, including collaborations between health and social services and the justice sector.

Trauma-informed treatment approaches also play an important role in the care of LGBTQIA+ women. Similarly to dedicated women-only services, specialised treatment approaches for this group are often exclusive to people who identify as LGBTQIA+ and seek to address substance use alongside other specific factors impacting their lives, such as homophobia, violence, social isolation and family problems.

It is important that services for pregnant and parenting women who use drugs are non-discriminatory and comprehensive. Anonymity may encourage women to seek care by removing the fear of reprisals. Interventions for pregnant women may address drug use, obstetric and gynaecological care, family planning, infectious diseases, mental health, and personal and social welfare. In some countries, specialist family centres and health visitor services exist to support drug-using pregnant women and parents of young children. Providing services to pregnant and parenting women can benefit both mother and child, improving parenting skills and having a positive impact on child development, as highlighted in the UNODC’s International standards on drug use prevention.

Opioid-dependent pregnant women are likely to need opioid agonist treatment and psychosocial assistance. Many pregnant women who use opioids want to stop once they discover they are pregnant, but withdrawal is not usually advised during pregnancy because it increases the risk of adverse outcomes for the neonate, including miscarriage. Studies suggest that both methadone and buprenorphine may be used in this context. Studies suggest that although buprenorphine is associated with superior neonatal outcomes, women already using methadone should not switch unless they are not responding well to the medication.

Multidisciplinary care programmes are provided in various countries. Some offer interventions to women who use drugs and their children from early pregnancy into childhood. Women may be provided with psychosocial support, interventions designed to empower them and build skills that will strengthen the family, and follow-up with case managers. Services may need to deal with practical concerns and provide childcare. Residential services may also provide child-friendly accommodation, enabling mothers to stay with their children.

Given the centrality of relationships to women, it is important to provide services that promote healthy connections with children, family members and significant others. Family involvement and links to the community can further enhance the effectiveness of drug treatment.

For women with co-occurring substance use and mental health problems, it is important that both issues are addressed. This requires a multidisciplinary approach, involving professionals from the drug treatment and mental health sectors collaborating and working towards agreed upon, common goals. Unfortunately, this does not always happen, and across Europe, drug use services, mental health networks and social services are often separated. Collaboration relies on the goodwill of stakeholders and cooperation at the individual level. Since many mental health disorders are more prevalent in women than in men, women who use drugs may be particularly disadvantaged in this respect (see Spotlight on… comorbid substance use and mental health problems).

The high rates of drug use, past abuse and mental health problems often found among women in prison suggest that gender-responsive, trauma-informed, integrated interventions are important as a way of addressing these issues, together with a focus on physical and reproductive health and infectious disease risk. Needle and syringe programmes, where syringes can be exchanged via slot machines, could also be considered. Opioid agonist treatment and psychosocial interventions are available for women with opioid dependence in some but not all prisons.

To prepare women for release from prison, interventions need to be considered in the following areas: housing and financial issues, vocational and life skills training, social support and family relationships, and referral to drug treatment in the community.

The barriers to care for women involved in the sex trade may be reduced by measures such as evening opening hours, mobile outreach services, childcare facilities and open-access support. A non-judgmental, empathetic approach, peer support and women-only provision are all recommended. Interventions from needle exchange to treatment and support with employment and housing are also important.

Ethnic and cultural aspects need to be considered when working with women from ethnic minorities. Outreach workers who can act as cultural mediators may encourage these women to attend and engage in treatment. Interpreter services or interventions delivered in the individual’s native language may be needed, and cultural aspects should be considered in matching women to treatment.

Internet-based drug treatment may provide an array of women-centred activities, alone or as an adjunct to other interventions. These may appeal to women not well served by specialised drug services.

With the increased differentiation in drug use patterns in Europe and the understanding that women are not a uniform population group, services that can address the different needs of women with drug problems are likely to be increasingly required if the difference in demand for drug services continues to narrow between men and women. For instance, more interventions may be needed for women who have problems with cannabis, non-medical use of medicines and polydrug use. Specific interventions may also be required following changes in drug use patterns in younger women, as well as interventions targeting older women, which for example address needs related to drug problems and menopause and ageing.

Funding presents a challenge in many European countries in times of budgetary restraint. Programmes for women may be neglected because women are a minority of service users. Conducting cost-effectiveness studies of interventions for women in diverse settings across Europe may help to secure long-term funding.

It is important that policies and practices are gender-mainstreamed, which means ensuring the centrality of gender perspectives and the goal of gender equality, and that women who use drugs participate in the planning, formation and development of the programmes set up to help them. Adopting a gender-responsive approach to drug problems benefits gender-diverse people including women, men, and transgender and non-binary people. Taking into account the varying needs of different genders in all aspects of health and social responses to drug policy, prevention, treatment and harm reduction would be in line with EU policy on gender mainstreaming, improve the effectiveness of provision and reduce inequalities.

European picture: availability of drug-related interventions for women

While no systematic data have been collected on the availability of women-only services or gender-mainstreaming responses to drug-related problems in Europe, there are a number of initiatives that exemplify such approaches. However, no information is available on the effectiveness of these interventions.

In Portugal, specific actions targeting women can be found in the main guiding documents on policy and interventions for addictive behaviours and dependency, namely the National Plan for the Reduction of Addictive Behaviours and Dependencies 2013-20. In France, the 2016 guide ‘Femmes et addictions’ (women and addictions) was designed to help frontline professionals improve the counselling and support provided to women. The guide also includes several recommendations for the care of pregnant women in opioid agonist treatment, and for family planning for women in opioid agonist treatment.

In Germany, outpatient addiction treatment facilities provide gender-specific services in many cities and metropolitan areas. For instance, LAGAYA in Stuttgart is a psychosocial addiction counselling and treatment centre for women and girls, as well as their relatives and other attachment figures. The FrauSuchtZukunft organisation in Berlin provides a range of services to women including psychosocial care, counselling, crisis interventions and outpatient addiction therapy. It also offers visits and counselling to women in prisons.

In Austria, Dialog, an outpatient addiction support organisation, has certain opening hours exclusively set aside for women, when no men are present at the centre. In addition, the Gesundheitsgreisslerei is an outpatient treatment centre run by women for women. It pursues a feminist approach, oriented towards women’s specific needs, and provides a safe space for women suffering from dependence on alcohol, illicit substances or both, who are in need of treatment, support or rehabilitation.

Gender-responsive harm reduction services have been implemented in Catalonia, Spain, by Metzineres, a non-profit cooperative committed to harm reduction, human rights and gender mainstreaming, which provides a safe shelter and harm-reduction responses to women who use drugs.

Interventions have also been implemented in Europe to address the needs of women in prison with drug-related problems. Needle and syringe programmes exist in some prisons for women in Spain and Luxembourg and in one prison in Germany.

Across Europe a number of services for pregnant and parenting women who use drugs also deal with a wide range of other issues, including, for example, obstetric and gynaecological care, family planning, infectious diseases, mental health, and personal and social welfare. Some services may address parenting issues, including women’s concerns that their children may be taken away, as well as providing childcare or child-friendly accommodation.

In Hungary the Józan Babák Klub cares for pregnant women or mothers with a child under 2 years using a three-step approach. In the first step, women contact the Józan Babák Klub self-help group to obtain information about the service. In the second step, medical, legal, social and psychological services can be used on an anonymous basis. A pregnant or parenting woman who engages in eight sessions of counselling receives a small monetary award per session. In the third step, the organisation arranges contact with health care, social or legal services and prenatal care for pregnant women. During the second and third steps, a member of the Józan Babák Klub self-help group will accompany women to the relevant services.

The Kangaroo project is a programme for parents within a residential setting in Belgium. It aims to enhance parents’ links with their children. Women are supported in their parenting role. During the day, children go to nursery, kindergarten or school, while mothers attend a therapeutic programme. The project provides information to parents, facilitates parent-child activities and thematic groups, offers individual consultation and ensures that parents are accompanied to appointments.

Implications for policy and practice

Basics

- Gender-responsive and trauma-informed services are needed to meet the needs of women with drug-related problems. These may make use of existing international tools to assess the inclusion of a gender perspective in health and social services.

- Staff in specialised drug and other health and social services who come into contact with women who use drugs can be trained to have the appropriate attitudes, knowledge and skills to enable them to provide high-quality care.

- Non-judgemental and safe environments for women with drug problems facilitate the accessibility of treatment and care.

- Coordinated and integrated services to address issues beyond drug use are needed. These may require embedding collaboration with other services (such as mental health and children’s services) into policies and strategies.

- Interventions for pregnant women and those that support women with children are important.

Opportunities

- Including breakdowns by sex in routine statistical data collection may enhance our understanding of drug use trends, sociodemographic factors and the issues faced by women within a given region. This is a crucial step in developing appropriate responses. Consideration may also be given to ensuring that such data include gender identities beyond the cis-gender classification.

- The participation of women who use drugs in the planning, formation and development of relevant policies and programmes may improve the services available and increase their reach.

- The implementation of the guidelines for the provision of services to treat pregnant women who use drugs has the potential to improve outcomes for both the mother and child.

Gaps

- Research that addresses gender issues and considers gender in all aspects of service design is needed in order to identify the types of intervention that are most appropriate for different groups of women.

- The need for and benefit of specific interventions for women who have problems with different drugs, including the misuse of prescription medicines and polydrug use, should be investigated.

- There is a pressing need for more research into and effective evaluation of approaches that respond to the needs of women who use drugs.

Further resources

EMCDDA

- Gender and drugs thematic page.

- Best practice portal.

- Women who use drugs: Issues, needs, responses, challenges and implications for policy and practice, 2017.

- Pregnancy and opioid use: strategies for treatment, 2014.

Other sources

- Pompidou Group – Council of Europe. Implementing a gender approach in drug policies: prevention, treatment and criminal justice, 2022.

- UNODC. Women and drugs. Drug use, drug supply and their consequences (World Drug Report), 2018.

- UNODC. Guidelines on drug prevention and treatment for girls and women, 2016.

- UNICRI. Promoting a gender responsive approach to addiction, 2015.

- WHO. Guidelines for the identification and management of substance use and substance use disorders in pregnancy, 2014.

- WHO. Gender mainstreaming for health managers: a practical approach, 2011.

About this miniguide

This miniguide provides an overview of what to consider when planning or delivering health and social responses for women who use drugs, and reviews the available interventions and their effectiveness. It also considers implications for policy and practice. This miniguide is one of a larger set, which together comprise Health and social responses to drug problems: a European guide.

Recommended citation: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2022), Women and drugs: health and social responses, https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/mini-guides/women-and-drugs-h….

Identifiers

HTML: TD-03-22-233-EN-Q

ISBN: 978-92-9497-841-7

DOI: 10.2810/95809